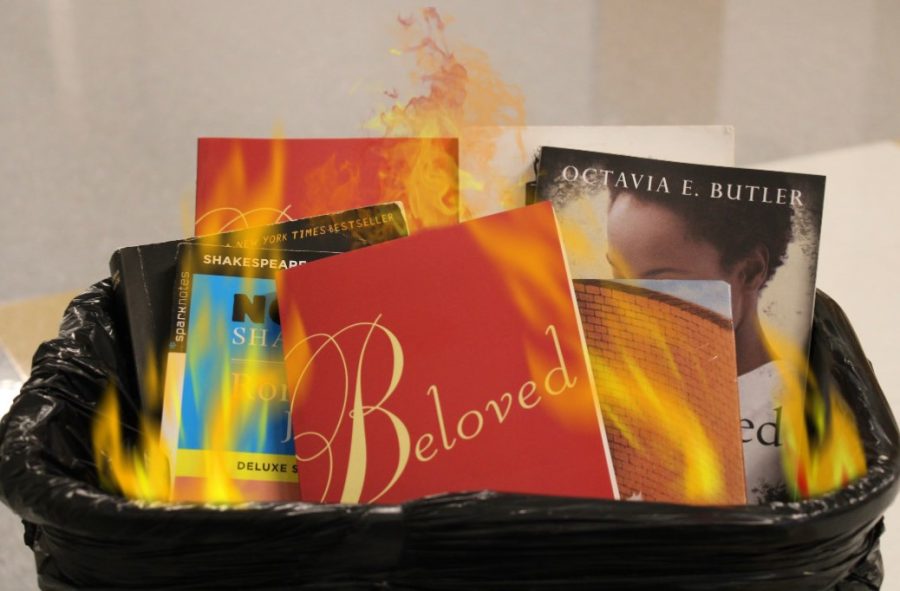

Senate bill forces new Loudoun policy covering sexually explicit material

A bill signed by Virginia Governor Glenn Youngkin has necessitated English classes in Loudoun county adopt a new policy covering sexually explicit material.

May 16, 2023

A new policy, titled “Policy 5055,” has gone into effect in English Departments across Loudoun County. The stated goal of the policy is to let parents know in advance if there is going to be sexually explicit content in the English curriculum. Teachers must send emails notifying parents of the explicit book in the lesson, and parents are to be given the option to ask for an alternate lesson plan. This policy came as a result of efforts by Governor Glenn Youngkin, who signed Senate Bill 656 on April 10, 2022 saying that all Virginia schools must adopt policies that alert parents of sexually explicit materials in the curriculum. Counties had to make their own specific policies in relation to the bill. Policy 5055 is unique to Loudoun County and was made and reviewed by Loudoun County officials.

This bill is the latest in an effort by Youngkin to expand the influence of state government into local school districts. In September of 2022, Youngkin issued an executive order which set-out a policy regarding transgender students in schools across Virginia. All school districts were to adopt new policies that were specific to their district, but in compliance with Youngkin’s Model Policy. In the policy, teachers were to notify parents if their child indicated they were or might be transgender.

After the state gave a set of guidelines for each county to make their own policy, a steering committee was formed in LCPS to manage the general course of making the policy. This steering committee included many different offices, such as: Secondary English and Reading, Elementary Reading and Writing, Media and Library Services, Social Sciences and Global Studies, Equity Office and Project management.

“The steering committee brought drafts of the policy for feedback of several citizen groups including, LCPS Equity School Board Subcommittee, Loudoun Educational Alliance of Families (LEAF), School Board Subcommittee on Curriculum and Instruction, Minority Student Academic Achievement Committee, among others,” said Dr. Michelle Picard, LCPS Supervisor of Secondary English and Reading.

There were many difficulties for Loudoun County officials when making the policy.

“Developing a policy and a regulation requires the involvement of several stakeholders, including administrators, teachers, central office personnel, citizen groups and the school board. To be thoughtful, this work requires different iterations of the policy and regulation drafts,” said Dr. Picard.

Teachers have had complaints about Senate Bill 656 and the resulting policies because schools were already transparent with parents before the law was put into place.

“I do think this policy is unnecessary,” said Lightridge AP English teacher Kirsten Cleary. “We [English teachers] are not hiding anything. This policy puts things to the forefront for parents to be concerned.”

English teachers have been posting their lesson plans and emailing parents whenever sexually explicit content shows up in lesson plans even before the policy was enacted. They have been reaching out to parents and students whenever there is explicit content in the curriculum, and have worked to make sure students are comfortable during lessons.

For example, Lightridge AP English teacher Lin Rudder said that when her class was reading “Handmaid’s Tale” she would “mark which chapters students can skip if they need to” and have “frank discussions” about some of the content with her students. Additionally,” Handmaid’s Tale” was originally marked as an 11th grade book, but Lightridge teachers made the decision to read it to seniors due to the explicit content. Both Cleary and Rudder post their lesson plans weeks before on Schoology, so parents and students can look at them if they need to.

With the new policy, Rudder is afraid that more teachers will return to the “whole class model” for reading books, instead of book club choices. Book clubs are a reading experience for students in which they are sorted into small groups based on what book they want to read. This allows students to discuss books without the teacher leading it, and allows students more freedom on what they want to read in class.

“With the whole class model, if a student is uncomfortable with something in the book, they don’t have other options. I think the power imbalance of limiting book club opportunities is troublesome to students,” said Rudder.

The policy provides a list of books to be checked by English teachers. Among the books are student favorites such as “Truly Devious,” “Aristotle and Dante Discover the Secrets of the Universe,” “One of Us is Lying,” “The Fault in our Stars,” and more. The list also includes classics such as “Romeo and Juliet” and “The Kite Runner,” which teachers have been using in lessons for years. Cleary says that” Romeo and Juliet” specifically is important to the classroom because it “delves into the importance of thinking before you act” and it highlights the “importance of having a trusted adult.” Lessons such as these, along with the added challenge of comprehending Shakespearean language and dissecting figurative language is incredibly difficult to replicate in an alternate lesson.

“Kite Runner,” a novel that has a graphic sexual assault scene, was not put on the list in the first iteration of the policy. After pushback from English teachers, policy-makers finally put it on the list of sexually-explicit books.

The policy also went into effect in January, when teachers had already gone halfway through their lesson plans. Due to this, there has been speculation that the people at the state level who wrote the original bill that was signed by Youngkin have had no experience in a classroom setting.

“Teachers do not have time in the middle of the school year to revamp lesson plans,” said Rudder. “That’s how I know nobody in education forced us to have to make this policy.”

Teachers had to team up all across the county to sort books into explicit and non-explicit categories. They created county-wide “sign-ups” in which teachers could volunteer to check over books deemed sexually explicit. If a teacher wanted to introduce a new book they would need to have another teacher sign off on it. Teachers said there were books they wanted to introduce this year, but couldn’t because they “couldn’t find additional teachers to vet them.”

“I felt uncomfortable sitting in my workplace with my colleagues and going through the definitions of ‘sexually explicit’ listed in the policy,” said Cleary.

The policy includes a definition of the phrase “sexually explicit,” in which the words “coprophilia, urophilia, fetishism,” “sadomasochistic abuse,” and “sexual bestiality” are used.

“The definition provided by the state for sexually explicit content in the law was based on adult definitions and involved words and actions that are not present in young adult literature,” said Picard. “This led to heightened concern.”

“I think part of the reason they made the definition so graphic is for shock value. They want parents to read it and be alarmed, even though we would never teach something like that,” said Rudder.

The policy states that teachers must be notified by parents only five days before an explicit lesson so that teachers can make up alternative lesson plans. Teachers say that five days isn’t nearly enough time to make an entire new lesson that has the same effect as the lesson previously planned. However, the school can’t enforce this part of the policy. If a student wants to drop out of a book halfway into it, they are allowed to. Rudder noticed that parents and students will often “ignore the book until the sexually explicit part.”

“It would be nice to have a resource ready to go provided by Loudoun County as an alternative packet or assignment,” said Cleary.

Teachers feel as though the Senate bill furthers the gap between staff and parents. It creates a narrative that teachers are not to be trusted enough to guide students through course material, and that they weren’t already taking the necessary steps to alert students and parents of content.

“At the end of the day I guess I’m troubled by this notion that we’re not communicating with parents,” said Rudder. “I think this bill is a self fulfilling prophecy. The more the government tries to say teachers and parents don’t get along – we won’t get along.”

Editor’s note: This article was updated on May 18 in order to include information provided by Dr. Michelle Picard.