Op-Ed: College Board history standards are outdated and inaccurate

College Board, the company in charge of determining what is taught in Advanced Placement classes, uses outdated and inaccurate standards, especially when it comes to issues that deal with religion.

February 27, 2023

Magic spells. You might associate these words with wizards, fantasy novels, and video games. However, these words were written in a Pre-AP class Nearpod detailing “Hindu core beliefs.”

The information given to students in classes at school about religions can be exaggerated and feel almost fake at times. Religions are taught in broad ways, and the information given isn’t always correct. While religions are very diverse and everyone practices it in different ways there should be, at the very least, some distinction made to tell students that religions are different and the information in the curriculum might not match up to what they’ve learned. It’s almost as if curriculum-makers expect everyone to fit into a box of religious practices.

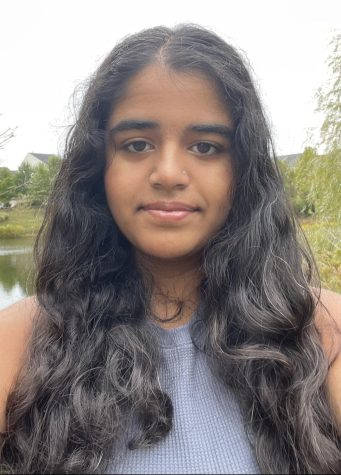

For some students, their religions aren’t taught at all. Suhani Jain, a freshman in Lightridge High School, had to advocate for her own religion to be taught in her Pre-AP world class.

“In general my religion [Jainism] hasn’t ever been in the curriculum,” said Jain. “It’s always been a sub-topic.”

Jain knew Jainism wouldn’t be in the plans for this school year. She took the initiative to make her own slideshow detailing the practices and origin of Jainism, which her teacher then showed to all of the Pre-AP classes.

History teachers are required by the College Board, the company that runs all AP classes and the SAT, to teach religions from the viewpoint of ancient civilizations. However, it’s not exactly clear to many people the differentiation between ancient and modern practices. There is no effort in the curriculum to let students know that what they’re learning has not been continued by the religion today, or simply isn’t a big part of a given religion anymore. This leads to misunderstanding about the major world religions that many people still practice. School is supposed to prepare students for the world after graduation- what will happen if students carry these misconceptions to their adult life?

“There are things [in the curriculum] that are a little bit fabricated. Maybe things that they had just pulled off the internet,” said Sahana Iyer, an officer of Hindu Student Association.

When teaching about something that is deep and personal to people today, it is necessary to teach it with respect, and this can only be done with substantial background knowledge. One reason why College Board might not be providing accurate information could be due to not enough in-depth research. Taking examples from the real books and mythology of the religion is one way to implement accurate and also in-depth learning in students.

It’s not the history teachers at Lightridge’s fault, as they are forced to teach the information given to them by College Board’s Advanced Placement organization.

“The best traditions of religious learning offer lessons for healthy intellectual and social development that prepare students to flourish,” College Board CEO David Coleman said in his article, “How religious learning helps us rethink the college race” published in the magazine “Christianity Today”. What he fails to highlight, is that religious learning is a conditional endeavor – there is healthy intellectual and social development, if and only if there is consideration and care taken into research of a designated religion. David Coleman’s organization is directly in charge of this possibility.

There are four things that College Board should be doing to be able to teach religions correctly: more research, give lessons directly from the source material, make sure that you have the support and buy-in of people who practice the religion being studied, and make sure that it is clearly stated in the curriculum that teachers must make a differentiation between old practices and new ones, as well as the internal diversity in religions. If these four things aren’t being taken into consideration, then teaching becomes harmful.

Iyer provided her own example of history teachings being quite damaging.

“When we were talking about the caste system for example, a lot of times they manipulate it so that the religion [Hinduism] is the main purpose of the caste system, which is not what it was originally for,” she said, referring to the AP standards. “The religion existed and then the caste system came to be.”

Sahana went to her history teacher and vocalized her concern with how it was being taught.

“When I say something [about religion] in class I’ll either have a student say ‘that’s wrong’ or ‘my parents taught me the wrong thing,’ and I don’t want to solicit either of those reactions because I don’t think either has to be true,” said Mollie Safran, a Pre-AP World teacher “I try to help students understand that what we learn in class is tied to the standards and if they practice their religions differently that’s okay, because religious practices are so diverse. I think that it’s also important for teachers to do their research and not to just take exactly what’s in the standards and put it on the slide. Try to watch videos from people who actually practice the religion to make sure you can explain it in ways that match up with them.”

Safran has made a special effort to make sure that nobody feels displaced by her history teachings. When she teaches religion, she makes sure to highlight the different ways people practice it, and make a special notice that students will be learning from a historical point of view. She has had the opportunity to have professional development in the area of religious learning as well.

Notice how something as simple as taking the time to make differentiation between modern and old practices, and highlighting the variation in religions makes a big change. It is not required for College Board or Virginia State Standards to completely change the curriculum, however it is necessary for them to understand their shortcomings, and to make notes in the curriculum that addresses that.

Safran went on to explain that not all history teachers have the opportunity to do extra research in the field of religion, and simply don’t have the time with their current workload to do courses on religious teaching. While it is important to make sure that you are teaching religions correctly, many history teachers are already being stretched thin, and doing more work than they already are is an arduous possibility.

This is why Safran encourages students to come to their teachers with their concerns.

“If you talk to your teachers about it, they will be absolutely receptive to repair harm,”

said Safran. “I know I would be very thankful for a student who voiced their concerns as opposed to not trusting me as a teacher for the rest of the year.”

Pre-AP teachers must use curriculum from the Virginia State Standards, and there have been many concerns with how a lot of ideas are represented by the standards. For example, you may notice that Lightridge history classes are behind on history lessons compared to other schools in the area. This is because the Virginia State Standards brushes over Eastern civilizations and focuses on civilizations such as Greece and Rome. Lightridge, however, decided to take their time to extensively learn all civilizations. This shows that there is definitely a Eurocentric civilization bias in the curriculum which could bleed onto Eastern religions and practices as well.

Kara Otto, an AP World teacher, has also noticed “discrepancies” in the way the standards represent information and the way students practice it. She, like Safran, highlighted the importance of student input.

“I think it would be cool to have groups of students meet with teachers and discuss what they want to be represented in regards to their religion,” Otto said. “I would love it if students had input in the curriculum and had a say in what is being taught.”

This is the most important thing – having input of people who actually practice a certain religion. While it might seem like a strenuous idea to take input on everything in the curriculum – there is no such thing as too much caution or attentiveness when it comes to teaching young and impressionable students. Students should not be more watchful of the curriculum than the actual curriculum makers.

When the state standards or College Board decides to teach a religion a certain way, you would think there’s not much to do about it. However, if Lightridge students were to actively voice their concerns about mis-teaching we could save a lot of misunderstanding and open the door to growth and companionship.

“If you want your religion to be represented, it’s up to you,” said Suhani Jain. “It’s your responsibility to advocate for the things you want to see in the curriculum.”